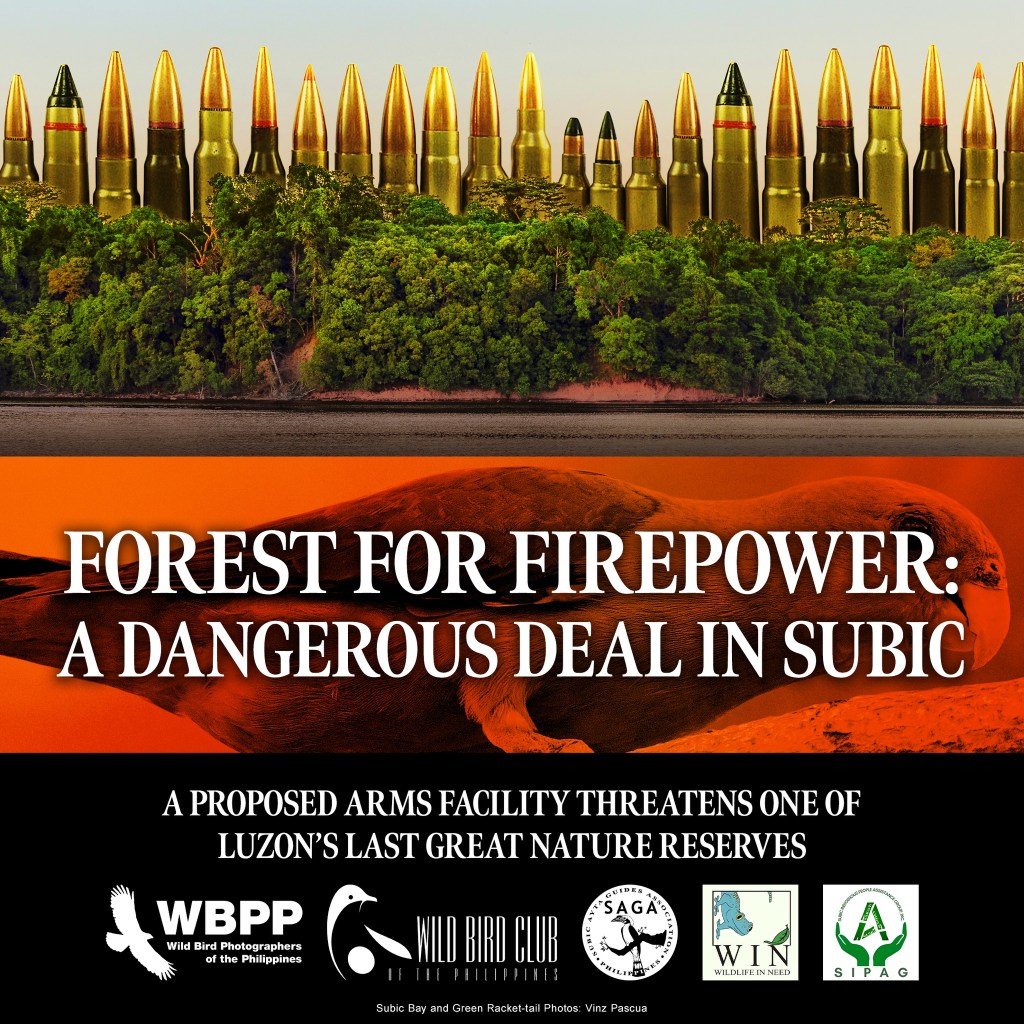

A proposed arms facility threatens one of Luzon’s last great nature reserves.

There is a stretch of land in the freeport zone of Subic Bay that sings with life — not from the noise of industry or the roar of trucks, but from the calls of hornbills, woodpeckers, kingfishers, and racket-tails, many of which are found nowhere else in the world. This is the Subic Bay Rainforest, one of the last remaining lowland forests in Luzon and a designated Important Bird Area (IBA) by BirdLife International through its local partner, Haribon Foundation.

Now, this protected area is on the brink of destruction — caught on a fault line where two opposing forces collide: nature conservation and militarization. The term “fault line” here is not geological, but symbolic. It is a fault line between two futures: one in which Subic thrives as a refuge for nature and people, and another in which it becomes a restricted zone for weapons and war.

A factory in the forest

Following the recent meeting last month between U.S. President Donald Trump and Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., plans for an ammunition factory and arms depot within the Subic Bay Freeport Zone were publicly floated as part of ongoing defense cooperation talks. All signs point to the likely location: the former U.S. Naval Magazine (NavMag) near Bataan Gate. This site is close to Ocean Adventure and within the Subic Rainforest corridor — one of the most biologically important bird habitats in the Philippines.

This area is not just a forest—it is a living sanctuary of irreplaceable biodiversity. Birdwatchers, bird photographers, and naturalists from around the world come to Subic to observe rare and endemic species that thrive only in these remaining lowland rainforests. Among the avian treasures are the Rufous Coucal (DENR Threatened), Indigo-banded Kingfisher (DENR Critically Endangered), Luzon Tarictic Hornbill (DENR Vulnerable), Rufous Hornbill and the elusive Philippine Eagle-owl (both IUCN Vulnerable and DENR Endangered).

Especially critical is the Green Racket-tail, a striking Luzon-endemic parrot now classified as Critically Endangered by the DENR and Endangered by the IUCN. Subic Bay’s forest is considered its last stronghold, with the latest 2024 BirdLife International estimate—building on research by UP Diliman professor Carmela Española—projecting just 300–800 individuals remaining, and only around 200–500 surviving in Subic and the Zambales Mountains. Unlike the Philippine Eagle, these birds have no dedicated conservation, research, or breeding programs. Their survival depends entirely on the continued protection of their natural forest habitat.

Subic’s rainforest is also home to iconic Philippine wildlife such as the Luzon-endemic Long-tailed Macaque, Northern Luzon Giant Cloud Rat, Philippine Warty Pig, Philippine Civet Cat, Philippine Sailfin Lizard, and the Golden-crowned Flying Fox, the world’s largest bat. These species, many of them threatened, rely on the forest’s undisturbed terrain and unique microclimate—conditions found in few other places in Luzon.

To destroy or fragment this critical ecosystem for industrial purposes would not only endanger these endemic species but also erase one of the last great living rainforests of Luzon.

The triple threat: habitat, access and displacement

The first threat is of an ecological nature. The construction of an ammunition factory in or near the Subic rainforest requires the clearing of roads, the erection of fences, the transportation of heavy equipment and, finally, the operation of high-security facilities. This means deforestation, noise pollution, light disturbance and vibrations — all deadly for nesting birds and sensitive forest animals. Once disturbed, the forest corridors become fragmented and many bird species never return.

In addition, the forest is the source of drinking water, clean air, organic food, natural medicine and a holistic lifestyle that makes Subic the most livable community. Proclamation No. 926 (Corazon C. Aquino, June 25, 1992) declared an area of about 6,261 hectares stretching from the northwestern slopes of Mount Natib down to Subic Bay as the Subic Watershed Forest Reserve. The proclamation was enacted to protect, conserve and enhance water yield and to limit unsustainable exploitation of the forest and disturbing land uses. In 2003, Proclamation No. 353, signed by President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo on March 31, 2003, amended the original proclamation and expanded the boundaries of the area to about 10,000 hectares.

The second threat is social and recreational. Once the area is declared a military-industrial site, it will almost certainly be closed to the public. For safety reasons, local birdwatchers, researchers, photographers and even residents of the surrounding communities could be restricted or evicted. One of the few remaining open forests on Luzon that is accessible to the public would be fenced off and silenced.

We’ve been through this before. Remember when TNT manufacturer Orica set up shop in the Freeport Zone? They closed off the road to Hill 394, a legendary birding spot known for sightings of White-fronted Tit and Rufous Hornbill, two very hard-to-find endemic species of the Philippines. Once the area was secured, the forest trail was closed indefinitely and one of Subic’s most valuable birding areas was lost. The last record of a White-fronted Tit in Subic dates back to 2018, and the Rufous Hornbill of Subic was last photographed in 2017. The precedent is clear — industrialization is closing off access and silencing nature.

The third and often forgotten threat is the displacement of the Aeta people. The mountains and forests of Subic, including the naval magazine, are part of the ancestral territory of the Aeta Magbukun — land they inhabited and protected long before the government declared it a free port. The Aetas gather forest resources, run small farms and have a deep cultural and spiritual connection to the land. A munitions factory will not only disrupt wildlife, but also risk forcibly relocating these indigenous communities and restricting their access. This would repeat a long pattern of militarized development and dispossess the very people who have protected this land.

It is also home to Subic’s most popular destinations such as Ocean Adventure, Zoobic Safari and Kamana Sanctuary. It is also what makes Subic the No. 1 tourist destination in Central Luzon and Asia’s top sports tourism destination. Local and foreign tourists, accompanied by Aeta guides, participate in ecotourism activities such as bird watching, forest bathing, mountain biking and adventure sports.

Destroying a forest is ecological violence. Displacing its inhabitants is cultural extinction.

A blow to ecotourism and education

Subic Bay is a global role model for what can be done with former military land. Since the closure of the US base in 1992, the area has been transformed into a center for ecotourism, scientific research, and environmental education. Birdwatchers, bird photographers, nature lovers, students, and researchers have hiked these trails and documented species that are disappearing elsewhere. Local guides, drivers, tour operators, and businesses have benefited from this quiet, sustainable economy.

A munitions factory in the rainforest will not only endanger biodiversity — it will wipe out decades of peaceful progress and destroy the foundation of one of Luzon’s few thriving natural economies.

What the government must do now

If the government insists on locating a US munitions plant, then it must act responsibly and with foresight. It must identify and allocate land for such a facility away from known bird and wildlife sanctuaries, natural habitats, and ancestral lands.

There is a far more suitable location: the vicinity of the former Hanjin shipbuilding complex, now run by Cerberus Capital Management, a US firm with alleged close ties to the White House. This facility has already been converted into a center for the repair of US Navy ships, and the US Pacific Fleet is expected to use it for regular maintenance work. Locating the munitions plant near this area — which is already heavily industrialized and secured — makes more logistical and strategic sense. It would consolidate defense infrastructure without encroaching on protected forest areas or displacing indigenous communities.

The government may also consider the coastal corridors from Zambales to Pangasinan and up to Ilocos Norte as alternative sites for the ammunition factory. These areas provide direct access to the sea and offer an opportunity to disperse development and job creation to the provinces, especially if the factory aims to surpass the scale of the largest U.S. ammunition facility. By locating it outside Subic’s protected zones, the project can still meet its strategic objectives without destroying a critical natural and cultural sanctuary.

The Subic rainforest, on the other hand, must remain untouched and unsealed. It is not a strategic buffer — it is a biological and cultural treasure. The government must publicly and unequivocally commit to preserving this protected area, ensuring public access to bird watching and nature trails, at the same time upholding the rights of the Aeta people, whose ancestral territory cannot simply be carved away in the name of foreign interests.

From protected area to deployment zone?

The Subic rainforest has a remarkable history. Even during the height of the US military occupation, the forests remained intact. In fact, the military presence unintentionally protected these areas from urban encroachment. The birds and animals never left. Iconic species such as the Indigo-banded Kingfisher, Luzon Tarictic Hornbill, Rufous Hornbill, Philippine Eagle-owl, the Critically Endangered Green Racket-tail, the Long-tailed Macaque and Golden-crowned Flying Fox, among others, continue to thrive in the quiet corridors of Subic’s rainforest.

After the Americans left in 1992, the forest did not need to recover — it was still alive and thriving. The trails were simply opened to the public, and what was once a secluded buffer zone became a paradise for birdwatchers, bird photographers, scientists, and ecotourists. Subic became a prime birding destination in Southeast Asia, not because nature had returned — but because it had survived.

And now, for the first time in decades, that resilience is under threat — not from war, but from a short-sighted agreement signed in peacetime.

A forest cannot grow back once it has disappeared

There are many places to build a weapons factory. But there is only one Subic Rainforest. A habitat where the birds and animals have never left, where the forest has never died, and where Filipinos, indigenous people, and foreigners alike marvel at the rich, irreplaceable life that thrives in its canopy.

Let us not be the generation that silences the rainforest. Let us not separate the forest from the people who love it and live in it. And let us not trade the calls of the parrots and hornbills for the hum of a machine that will never know what it has destroyed.

Subic Aeta Guides Association (SAGA)

Subic Indigenous Peoples Assistance Group (SIPAG)

Wildlife In Need Foundation – Philippines (WIN)

Wild Bird Club of the Philippines (WBCP)

Wild Bird Photographers of the Philippines (WBPP)

Leave a comment